The Frankenhuis Collection

This website is dedicated to the enormous contribution of Maurice Frankenhuis, who purposefully built a collection intended to document the history of the two world wars, and commemorate the Holocaust of European Jewry.

The collection serves as a resource of historical information, and guidance to teach about the evils of hatred and discrimination.

This website shows a few examples of archives (diaries & memoirs) and artifacts from the Frankenhuis Collection.

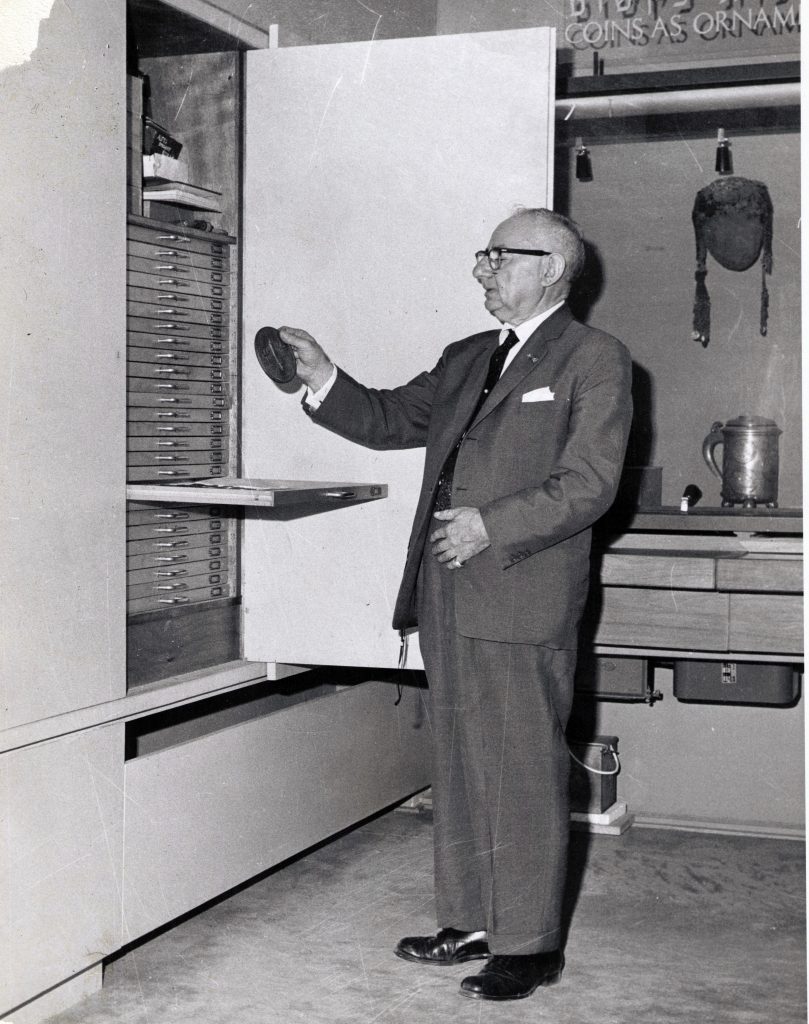

Maurice Frankenhuis authored his diaries and memoirs, collected memorabilia, posters, coins, medals, documents, letters, autographs, photographs, and other artifacts relative to the two World Wars 1914 – 1918, and 1939 – 1945, and the Holocaust of the Jewish people in Europe and his homeland, the Netherlands.

using this rubber ink stamp and his letterhead stationery.

The vast collection reflects Maurice Frankenhuis’ lifelong dedication to make the world a better place for humanity. The collectible objects and documented narratives are educational tools he used to preserve an authentic record of a world conflicted by good and evil. Inherently, the collection exemplifies Maurice Frankenhuis’ personal guiding principles and determination to promote respect for all human beings, living with integrity, values of religious faith, benevolence and generosity. The story of his lifetime told by his collection is at the same time an important lesson for the future and a significant contribution to the archives of history documenting the turbulent years of the 20th century and its aftermath.

Museums & Exhibits

The donations of coins, medals, and posters have been deposited at major museums across the globe. Virtually the entire collection of World War I has been given to the world’s most prominent institutions: the British Museum in London, England, and the Columbia University Library of Rare Books and Manuscripts in New York.

The majority of Maurice Frankenhuis’ World War I medal collection as well as a significant portion of his World War II medal collection was given to the Kadman Numismatic Pavilion of the Eretz Museum in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Other museums and institutions that received numismatic material include the Jewish Museum and the American-Israel Cultural Foundation, both in New York.

Some documents shared and incorporated into the libraries of the the YIVO Institute, the Weiner Library, the Leo Baeck Institute and others, are now available to museums all over the world with the advent of document imaging and international archive sharing.

With the centennial of World War I, all of the recipient museums curated a specialized exhibit from the donated medals and posters for public display. See Museums & Exhibits for more information.

Archives of Diaries & Memoirs

From the beginning of unrest in Europe during the 1930’s, Maurice Frankenhuis began to record his diary of historical events in Europe, and his own family’s experiences in the Netherlands.

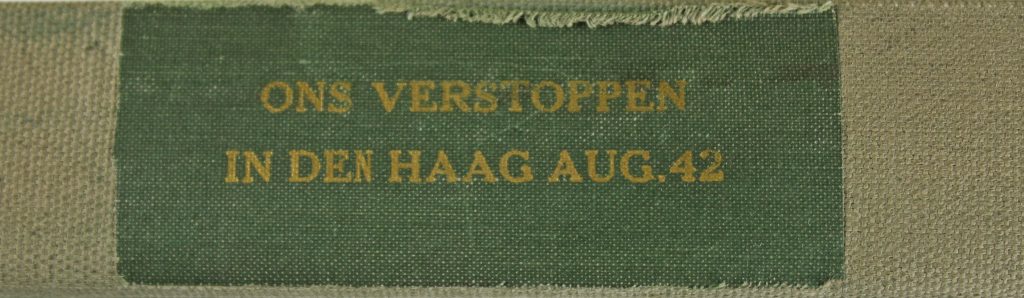

Volume 1: Hiding us in the Hague [July 23, 1942 (Tisha B’Av) – March 28, 1944]

Volume 2: Prison [March 28, 1944 – April 20, 1944]

Volume 3: Westerbork [April 20, 1944 – September 4, 1944]

Volume 4: Theresienstadt [ September 6, 1944 – June 6, 1945]

Volume 5: Flash – After the War (Return to The Hague) [June 27, 1945]

Volume 6: Letters on the war after liberation

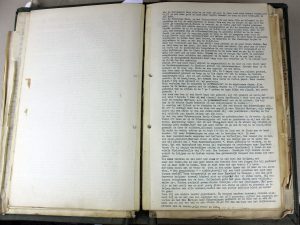

Under adverse circumstances, when in hiding or in concentration camps, he maintained his diary using a secret code methodology he invented to assure no one would be able to decipher but him. It is a remarkably detailed account of all what he endured and observed, totaling approximately 1500 pages.

After the liberation, he spent two years decoding his writings into Dutch, converted to typewritten archival paper pages, and bound into individual volumes for long-term preservation. They were embossed with titles in Dutch.

Page of Diary and Title on spine: Hiding Us in the Hague Aug. (19)42

After the diaries were transcribed into Dutch, he began to write his memoirs. These were typewritten in English and include some recollections from the diaries, but mostly reports on his activities and findings during the two decades after the liberation until his death. There are many personal stories, accounts of interviews and research of the Holocaust which was generally unavailable or inaccessible. The compiled chronicles occupy 24 volumes and hundreds of folders. Much of the source material came from his regular visits to Europe, particularly to historical landmarks of the war, accompanied by photographs. He maintained copies of all his correspondence and commentary on news events. He was a one-man search engine well before the arrival of the internet and Google!

Artifacts & Art

Maurice Frankenhuis understood the significance of objects to bear testimony to the experiences of the persecution of the Jews in the Holocaust. From the time he was imprisoned after discovery in hiding, followed by incarceration in two concentration camps (Westerbork in the Netherlands and Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia) he inconspicuously carried and discretely hid his suitcase with stored collected items, that should he survive, would provide evidence of the many tribulations he and others endured. The suitcase had a secret lining, where he also deposited important documents. He gave instructions to trusted inmates that should he not survive, the suitcase should be safeguarded until the liberation for the future. Fortunately, he and his family, and his suitcase all survived.

Published

Maurice Frankenhuis authored and made available to the public several publications which at the time he must have felt a particular urgency to disseminate. The very first is his Catalog of Medals, relating to the extensive World War I medal collection he was able able to assemble. A citizen of the Netherlands, he was at the right place at the right time to be able to procure medals from Germany, France, Great Britain and the U.S.A. while others could not due to restrictions imposed by the belligerent countries.

Another example is the publication of his visit to concentration camp Westerbork and interview with its Commander Gemmecke just after the war. This short but vivid account is unique in its timing, and his quest to confront the Commander of the camp with details of the inmates’ experience, without ever disclosing his identity, in order to document it for the public record.