Is Paris Burning?

Notes by an Eye-Witness to the Burning of Rotterdam,

an Assignment carried out by Lt. Col. von Choltitz

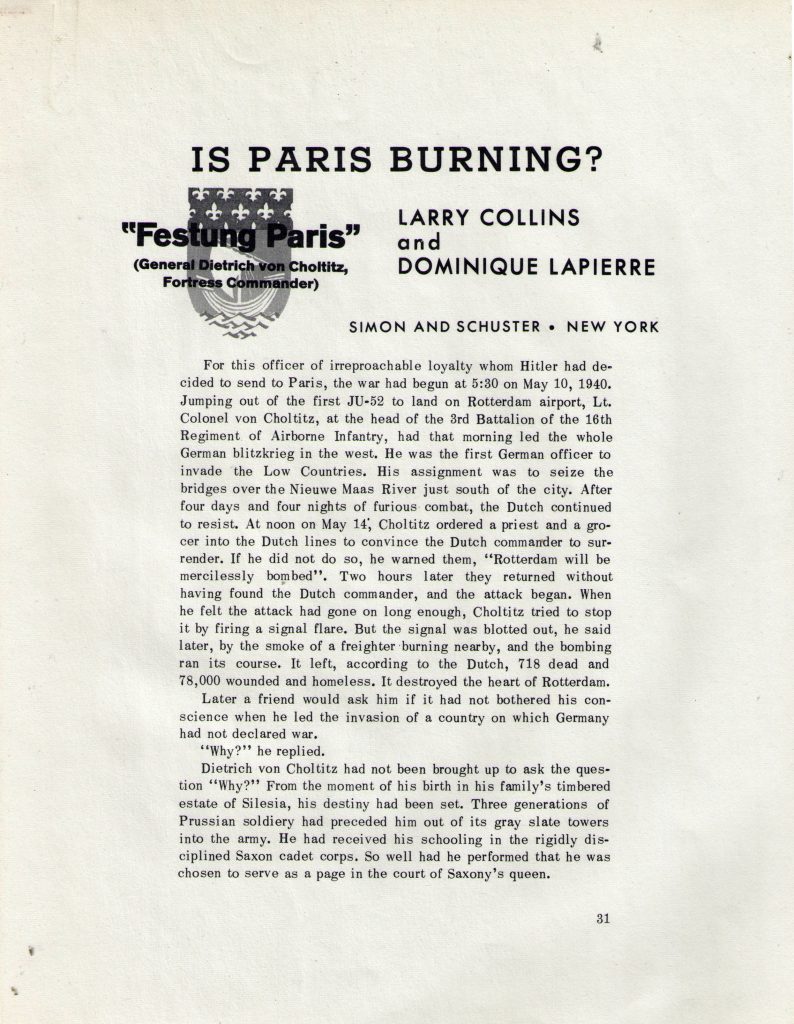

IS PARIS BURNING?

LARRY COLLINS and DOMINIQUE LAPIERRE

SIMON AND SCHUSTER NEW YORK

(General Dietrich von Choltitz, Fortress Commander)

For this officer of irreproachable loyalty whom Hitler had decided to send to Paris, the war had begun at 5:30 on May 10, 1940. Jumping out of the first JU-52 to land on Rotterdam airport, Lt. Colonel von Choltitz, at the head of the 3rd Battalion of the 16th Regiment of Airborne Infantry, had that morning led the whole German blitzkrieg in the west. He was the first German officer to invade the Low Countries. His assignment was to seize the bridges over the Nieuwe Maas River just south of the city. After four days and four nights of furious combat, the Dutch continued to resist. At noon on May 14, Choltitz ordered a priest and a grocer into the Dutch lines to convince the Dutch commander to surrender. If he did not do so, he warned them, “Rotterdam will be mercilessly bombed”. Two hours later they returned without having found the Dutch commander, and the attack began. When he felt the attack had gone on long enough, Choltitz tried to stop it by firing a signal flare. But the signal was blotted out, he said later, by the smoke of a freighter burning nearby, and the bombing ran its course. It left, according to the Dutch, 718 dead and 78,000 wounded and homeless. It destroyed the heart of Rotterdam.

Later a friend would ask him if it had not bothered his conscience when he led the invasion of a country on which Germany had not declared war.

“Why?” he replied.

Dietrich von Choltitz had not been brought up to ask the question “Why?” From the moment of his birth in his family’s timbered estate of Silesia, his destiny had been set. Three generations of Prussian soldiery had preceded him out of its gray slate towers into the army. He had received his schooling in the rigidly disciplined Saxon cadet corps. So well had he performed that he was chosen to serve as a page in the court of Saxony’s queen.

“IS PARIS BURNING?”

Notes by an Eye-Witness to the Burning of Rotterdam,

an Assignment carried out by Lt. Col. von Choltitz

Time gives to the design of history — however haphazard its connections — a semblance of order. The cause-and effect structure, which historians seek, can be all askew, but elements of time do provide a kind of system and bear out the old saw, “History repeats itself.” More often than not, it is not a repetition, but a rhythm created by the spacing out of events. The configuration may be accidental but it is intriguing.

For instance:

On August 3, 1914, Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm II invaded Belgium, in violation of the treaty with the Big Powers to guarantee the neutrality of small nations.

26 years later, on May 10, 1940, Germany under Adolf Hitler, invaded the neutral nations of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxemburg, without warning or provocation. This act of criminal warfare was carried out by Lt. Col. von Choltitz who commanded the bombing of Rotterdam.

26 years later, on November 6, 1966, Dietrich von Choltitz gave up the ghost – not on the battlefield, but in his bed in Baden-Baden.

November 6, 1966 was also the week when the Rene Clement film, “Is Paris Burning?” opened at the Criterion Theatre in New York City. As we know, this is based on an account of the liberation of Paris, written by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre. In both the book and the picture von Choltitz plays a major role as the German commander in whose hands rested the fate of Paris. Thus, the character and behavior of this Nazi officer during a historic segment of his career will be made familiar to millions of readers and viewers through the fictional means of book and movie.

There is an extensive bibliography of other books and articles that deal with this period — perhaps compiled with greater authenticity but all seem to come to the same conclusion: “Paris was NOT for Burning.”

In August 1944, when Hitler issued orders to hold or to burn Paris, FIRE (either as flames or smoke or ashes) had become a familiar part of the European landscape. It was seen in the rubble of buildings and stretches of earth scorched and smoky, and the charred forests.In its most macabre aspect it left its mark on piles of human flesh at the crematoria of Auschwitz.

1944 was the year that my family and I were interned at Theresienstadt, a concentration camp operated by the Nazis in Czechoslovakia. We had been arrested in our homeland, the Netherlands, and had undergone the dehumanizing experience of transport like cattle in a freight car.

This was a step in the chain of events that had begun with the invasion of the Netherlands by the Germans on May 10,1940. On May 14, I had witnessed the bombing of Rotterdam, where I was stationed in connection with my business. This single attack left 718 dead and 78,000 wounded and homeless and the city completely destroyed. By the time the war was over, the Netherlands (always neutral) suffered the loss of close to 200,000 people, of whom 104,000 were Jews. The royal family had fled at the beginning of the German attack and were living abroad.

The first one to have set foot on Dutch soil to conduct these atrocities was Lt. Col. Dietrich von Choltitz (to be promoted to General for bombing Sevastopol in 1943). Set against all the grim incidents of the Nazi occupation – the enormity of which appears to grow greater with time – certain individuals who acted as Hitler’s diabolic agents will forever occupy a place in my personal gallery of monstrosities and continue to feed my abhorrence. Here I have placed and shall forever hold von Choltitz. Perhaps to the French people, he will be remembered as a “‘minor-league” enemy, but for the Dutch he can never be whitewashed through any book or film. They will never forget that he was the first German to lay waste to their fatherland.

Perhaps I should have boycotted the film. But instead I went twice to see it. I was eager to observe how this demon would be brought to life in his role as the commander of the beleaguered Paris. I was surprised to note the “unprejudiced” tone of the movie-makers. In the book too he was given the “handle-with-kid-gloves” treatment. On the book jacket the authors are seen photographed with him, and they acknowledge their gratitude for his cooperation in giving them a good deal of information and documents.

For me, it is difficult to reconcile such gentility with the knowledge that this is the same person as the heedless mirauder, whose presence and signals activated the destruction of cities, where it took but a few hours to kill and maim for life countless human beings and destroy the fruits of their labor. In the film he appears suave and refined, hired (lately somewhat against his will) by his Führer to erase the most beautiful, the most richly civilized city, in the world, for which people of all nations had a special love.

The film (and the book too) leads the viewer to believe that most of the Nazi invaders — whether members of the Wehrmacht, the Gestapo, the troops and other officials — had become infected

with such a romantic regard for Paris, that it would hurt them profoundly to molest it. And, of course, we see Choltitz himself succumbing to this Lorelei of the Seine, and he moves from his military headquarters to a deluxe suite at the Hotel Meurice where he can more thoroughly enjoy the city’s attractions.

This benign portrait strikes me as most unrealistic. If Choltitz did appear to improve as a human being, I believe it was not due to a change of character, but to a sense of expediency. A glimmer of the truth had begun to penetrate his Prussian shell. He had seen Hitler face to face when he received the Paris assignment. He had had the shock of recognizing his idol as a madman. He had failed to get the moral uplift he was counting on getting from Hitler, and now there was nothing that would counteract his fatal pessimism concerning Germany’s future. Everything was “Kaput.”

He suspected that Hitler’s frenzied commands and his final ultimatum: “Paris must not fall into the hands of the enemy, or if it does, he must find there nothing but a field of ruins,” were an outburst of desperation.

The tide had turned on the Eastern front in the winter of 1943. The German armies were disrupted in retreat, with the Red Army in a long, hot pursuit. Now it was 1944: The Western Front was in operation with the invasion by the allies on June 6, 1944. The French, American and British forces were moving closer to Paris, where the Germans were growing frantic about the delays in arrivals of reinforcements. Their defenses were toppling. How could they sustain the siege of Paris?

It was so different from the conditions at the beginning of the war. Then the German generals, under Hitler’s spell, saw only a line of uninterrupted conquest. It was “Deutschland uber alles,” from here to infinity. The gospel of the Brown Book was working. Even now, they could turn back the pages and gloat over Rotterdam, Coventry, Sevastopol, Warsaw. Stalingrad had been a hard pill to swallow. By 1944 doubt and disillusionment began to corrode the base metal of their daring. They realized they had met their Nemesis.

By August 9, when he arrived in Paris, von Choltitz may have realized he had had enough. He observed his subordinates, too, established in luxurious villas in the Parisian suburbs, enjoying the best wines served in exquisite goblets, working off their hostilities through music performed on conveniently placed Bechsteins. These dilettantes showed little resemblance to the Nazi warriors of the past, the sadists of the Warsaw Ghetto or of Auschwitz. Life in Paris seemed to have transformed them (at least in the movie), like in the German Märchen, from beasts into gentle princes who relished the beauties surrounding them.

The General had to put up with the needling of some of his conscientious comrades, who kept reminding him of Hitler’s orders. In fact, new commands came through from the irate Führer himself. Therefore von Choltitz ordered Paris to be thoroughly wired for destruction. No bridge or public building was overlooked. Only the match was needed to produce a total conflagration. The order for that could come from but one person, he warned from himself, the Commander General Dietrich von Choltitz – and in writing!

But he kept on waiting, and then it was too late. According to the story, he was most cooperative with the neutral Swedish consul, Raoul Nordling. He and the consul kept all their “gentlemen’s” agreements which resulted in a play for time and permitting a French emissary through the lines with messages that would hasten the French and American armies into Paris. In fact, this miracle came to pass only 15 days after von Choltitz had arrived. His sacred mission was frustrated.

In the short period of his occupation of Paris, Choltitz also had been able to appraise the opposition within the city. On August 12, three days after his arrival, the French railway workers struck, paralyzing the railway system. The postal and telegraph workers followed this example. On August 19, the Paris police who had been divested of their arms by the Germans — managed nevertheless to effect a total mobilization and to seize the prefecture of the police, which they used as headquarters and an effective base of operations for sabotage and resistance. Their control spread to the principal ministry buildings, the city hall and other important strongholds. They even stole the press away from the Germans and were now able to keep the citizenry informed and under Free French order. Barricades appeared in the street, after the historic tradition of other insurrections since the days of the French Revolution and the Paris commune. The Parisians were geniuses at improvisation.

Bicycles and handcarts moved supplies from one point of siege to another: old bedsteads, cradles, stoves, anything that had weight enough to stay on the ground, supported the sandbags dragged down from the attics. And there was a good deal of equipment captured from the Germans. The partisans now had guns and trucks. They fired from behind windows, rooftops and over the street barricades.

While General von Choltitz waited to give the word to set off the dynamite charges, he knew the resistance was growing. He did not act. And on August 24 the armored divisions of the Free French and Americans rolled across the bridges into the city and removed the last vestiges of the German power.

Even though the General failed to behave true to form — the Nazi form — the film also failed to eradicate from my mind my impression of him as a fiend. Representing him as well mannered, of excellent breeding, could not change my impression of him as a murderer and a war criminal, for which I had plenty of evidence. My recollections are indelible, but I also have records in my files, as I am a collector of historical items.

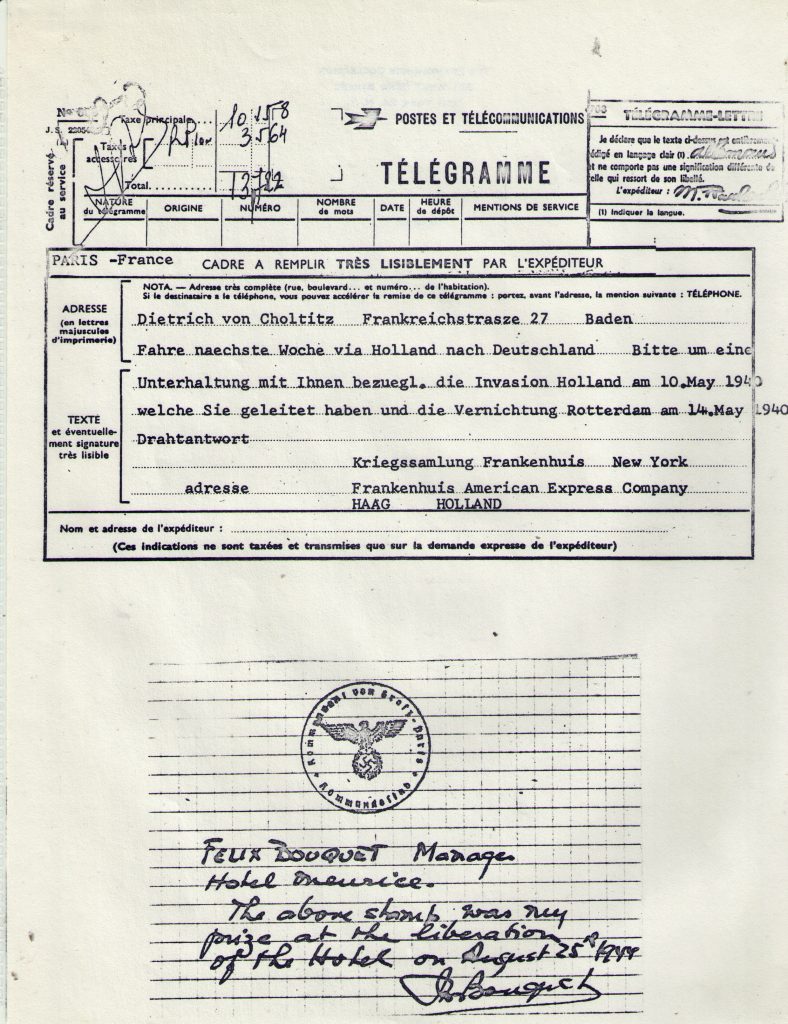

It has been my practice, moreover, to try to confront these loathsome characters whenever and wherever I can. My experience in reference to Choltitz has been as follows: On October 2, 1962, while staying at the Hotel Meurice, Paris (formerly von Choltitz’s headquarters), I cabled him offering to come to Baden Baden for an interview. My cable made no mystery of my feelings, and it contained some reference to his barbaric invasion of Holland as the topic that I wanted to discuss with him. The General did not answer me. In other cases, my adversaries had the courtesy to reply.

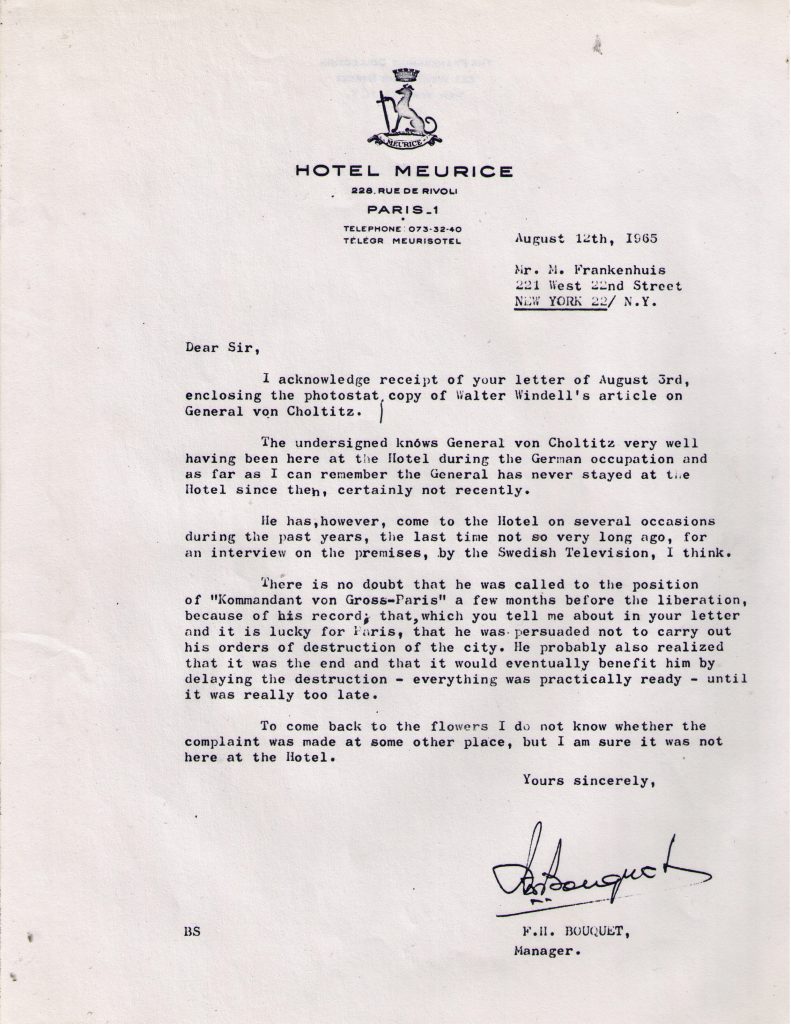

Another postscript concerning this Nazi may be of interest: On July 23, 1965, Walter Winchell wrote in the New York Journal American: “The Nazi General in charge of the occupation of Paris recently returned for a visit. He stayed at the Meurice Hotel, which had been German Headquarters. He had the gall to complain to the management because there were no flowers in his room to greet him.”’

I mailed this item to Monsieur F. H. Bouquet, the manager of the Hotel Meurice. His reply of August 12, 1965 I prize as an interesting document in my Choltitz file. After denying that the General stayed at the Meurice in recent years, he admits that he did come as a visitor. ..the last time not so very long ago for an interview…by the Swedish Television . .”

M. Bouquet, who was personally acquainted with the General during the occupation, further divulges: “There is no doubt that he was called to the position of ‘Kommandant von Gross-Paris’ because of his record which you tell me about in your letter. It is lucky for Paris that he was persuaded not to carry out his orders of destruction of the city. He probably also realized that it was the end and that it would eventually benefit him by delaying the destruction – everything was practically ready until it was really too late.” [underlining mine]

It seems to me that M. Bouquet’s verdict is a sound one. As to von Choltitz, his public statements can be appraised to indicate that he hoped “desperately to be remembered as a true hero of the liberation of Paris.” Finally, he wanted, above all to have “the world…leave him in peace (Frieden!).” He now has his peace in death, a death different from that which he inflicted on thousands of his victims.

Maurice Frankenhuis

221 West 82 Street

New York, N. Y. 10022

HOTEL MEURICE

- RUE DE RIVOLI

PARIS-1

TELEPHONE 073-32-40

August 12th, 1965

Mr. M. Frankenhuis

221 West 22nd Street

New YORK 22/ N.Y.

Dear Sir,

I acknowledge receipt of your letter of August 3rd,

enclosing the photostat, copy of Walter Windell’s article on

General von Choltitz.

The undersigned knóws General von Choltitz very well

having been here at the lotel during the German occupation and

as far as I can remember the General has never stayed at the

llotel since then, certainly not recently.

He has, however, come to the Hotel on several occasions

during the past years, the last time not so very long ago, for

an interview on the premises, by the Swedish Television, I think.

There is no doubt that he was called to the position

of “Kommandant von Gross-Paris” a few months before the liberation,

because of his record, that,which you tell me about in your letter

and it is lucky for Paris, that he was persuaded not to carry out

his orders of destruction of the city. He probably also realized

that it was the end and that it would eventually benefit him by

delaying the destruction — everything was practically ready – until

it was really too late.

To come back to the flowers I do not know whether the

complaint was made at some other place, but I am sure it was not

here at the Hotel.

Yours sincerely,

F.H. BOUQUET,

Manager.