Maurice Frankenhuis

From his grandfather, Maurice Frankenhuis as a boy inherited a passion for collecting as well as a substantial nucleus of documents, coins and medals. With that start, his ambition took wings. He always seemed to have that inborn gift which denotes the collector, an amalgam of curiosity, enthusiasm, and energy.

He was born on February 24, 1894 as a Dutch citizen, Holland having been for generations the birthplace of his forefathers. Of Jewish faith, his family, traditionally, respected learning and took pride in guiding its youth into righteous and fruitful paths. When, at age 18, he had absorbed his share of excellent moral training and practical instruction, young Maurice was packed off to Manchester, England, to master both the English language and the fundamentals of the cotton business as a basis for his future occupation.

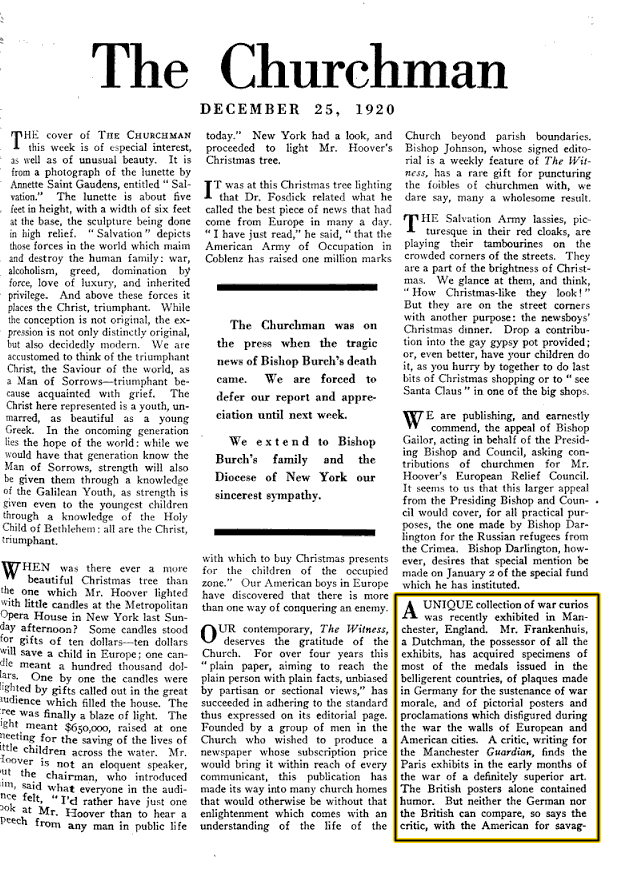

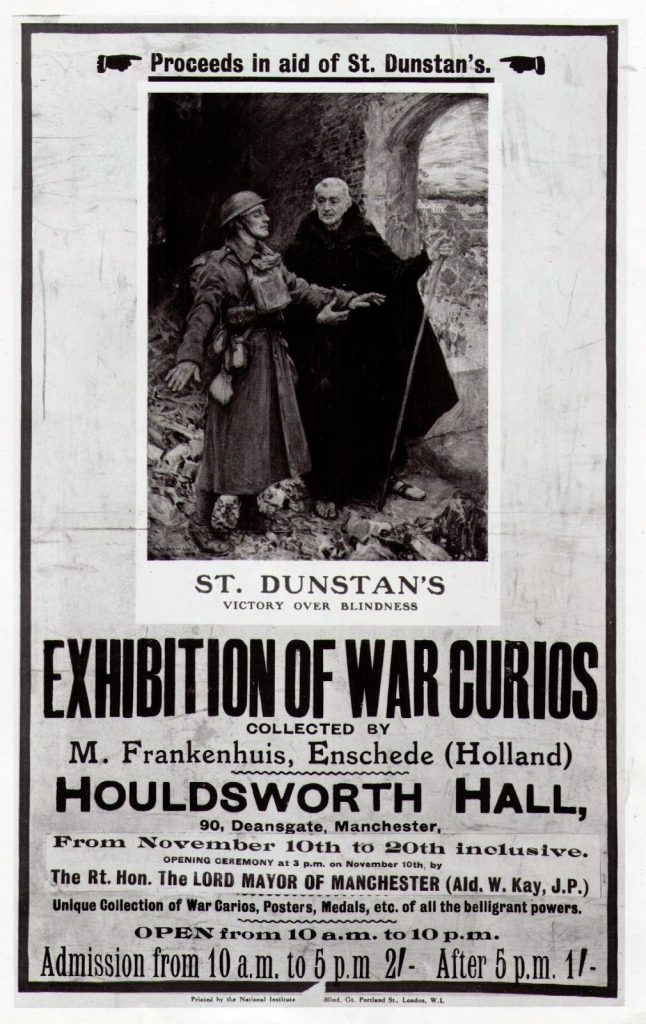

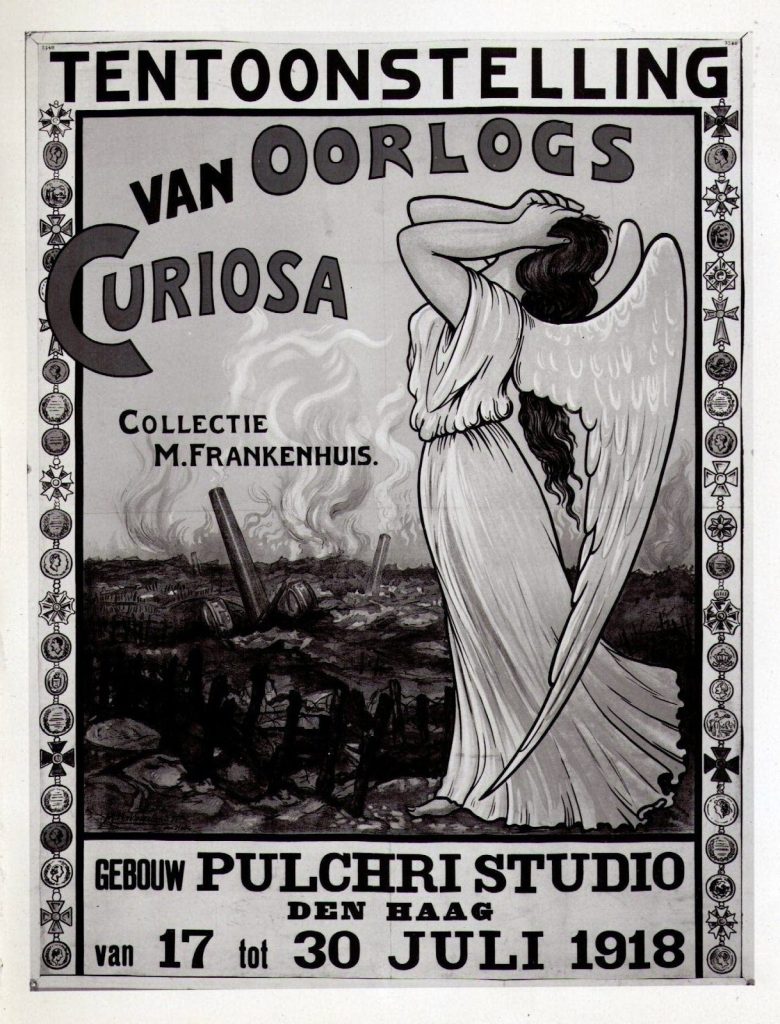

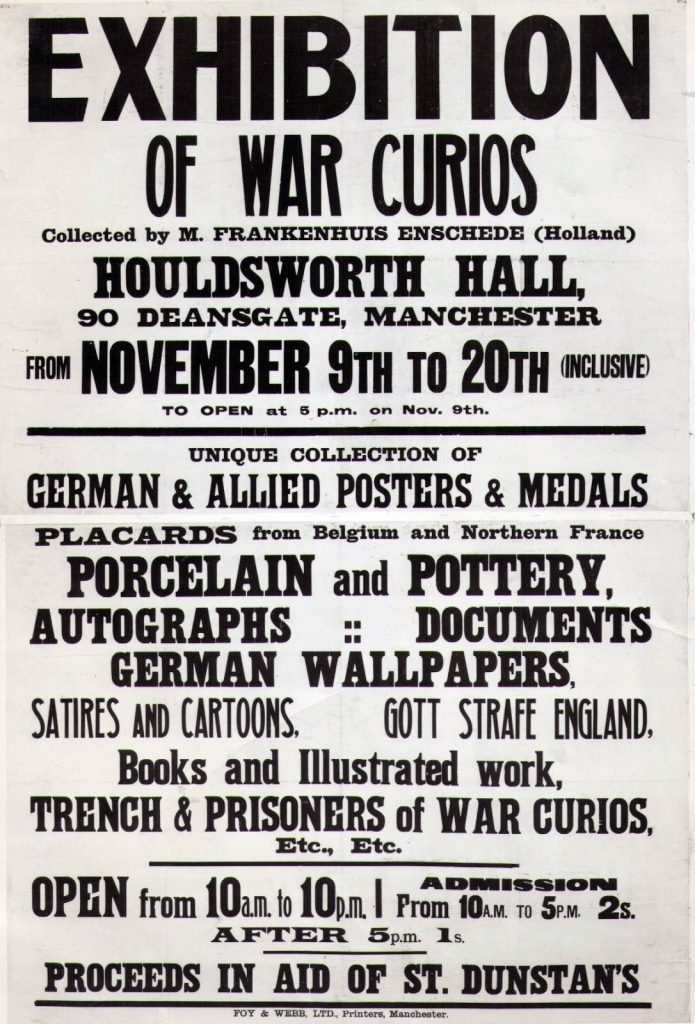

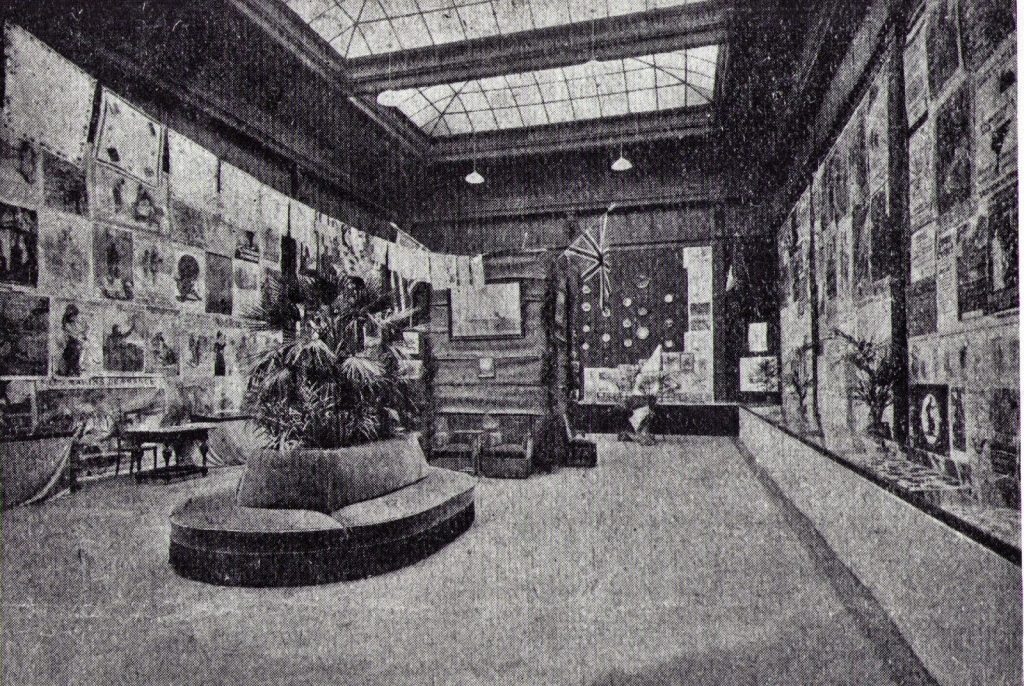

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 necessitated his return to Holland, and he made the most of his country’s neutrality to secure war medals from both the Allied and the German sides, establishing his first permanent collection. By 1916 he was invited to show at charity exhibitions. One of the early events at the Hague – then as now the glittering seat of the foreign embassies – attracted the attention of Sir Walter Townley, the British Ambassador, who was anxious to acquire certain rare items.

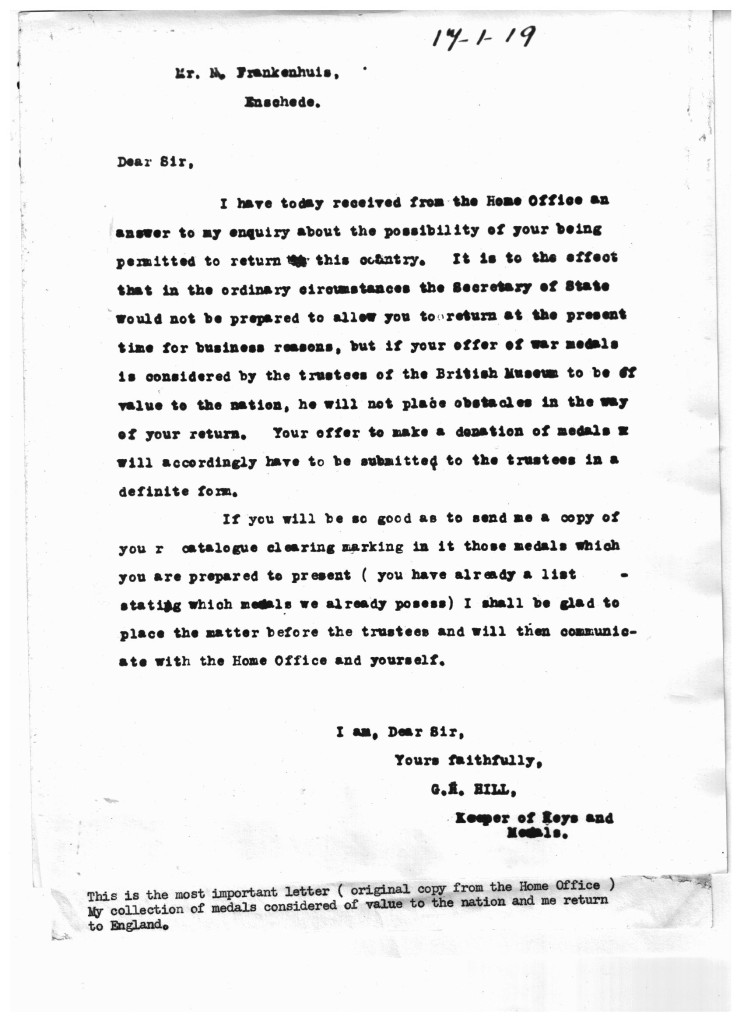

The British Ambassador intervened with his government on behalf of young Frankenhuis who had expressed his desire to return to England. As it was then but shortly after the end of the war, this privilege was generally denied to foreigners. However, through Sir Walter’s good offices, the young collector soon heard officially from the British Secretary of State that they would “not place any obstacles in the way of your return” [to England] …should “your offer of war medals… be of value to the nation.” The Trustees of the British Museum ruled in his favor, deeming his presence, as the donor of the war medals, of “value to the nation.” He happily embarked for England, laden with his treasures destined for the British Museum.

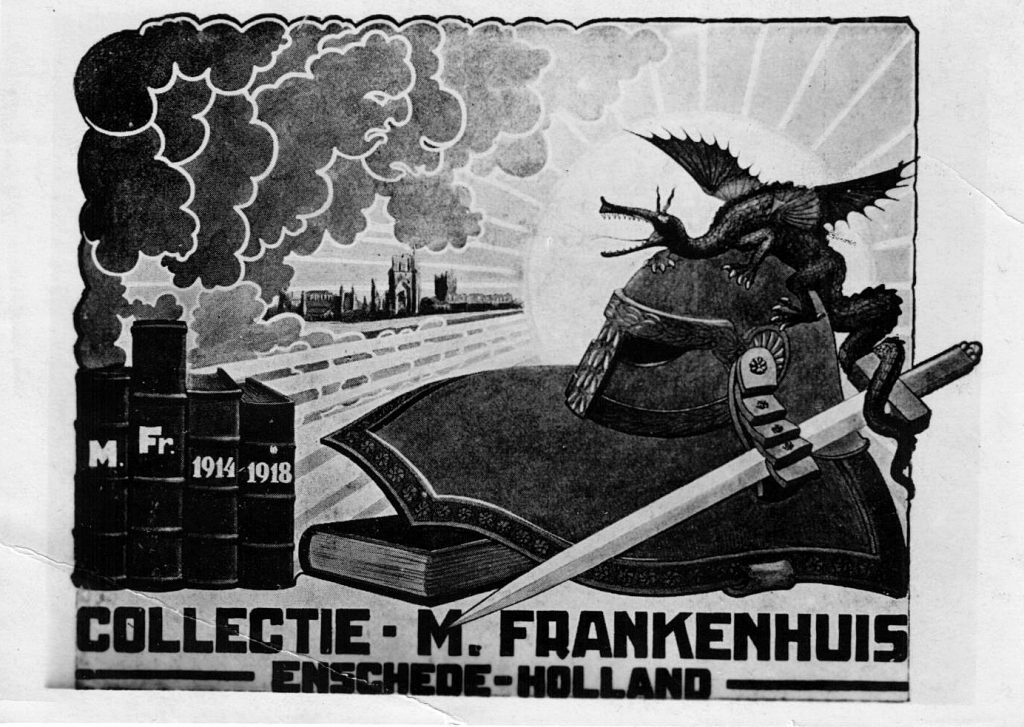

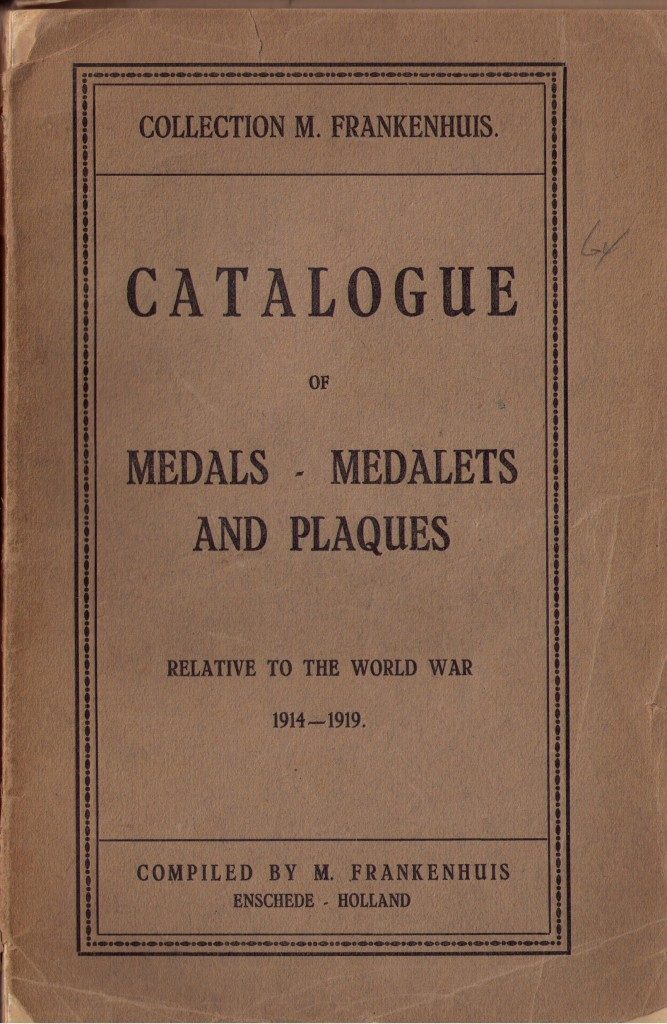

By 1918, his private collection was so extensive that his “Catalogue of Medals and Plaques, relative to World War 1914-1918” was printed in Dutch, English and French. To this day it is a valuable reference work for numismatists and historians.

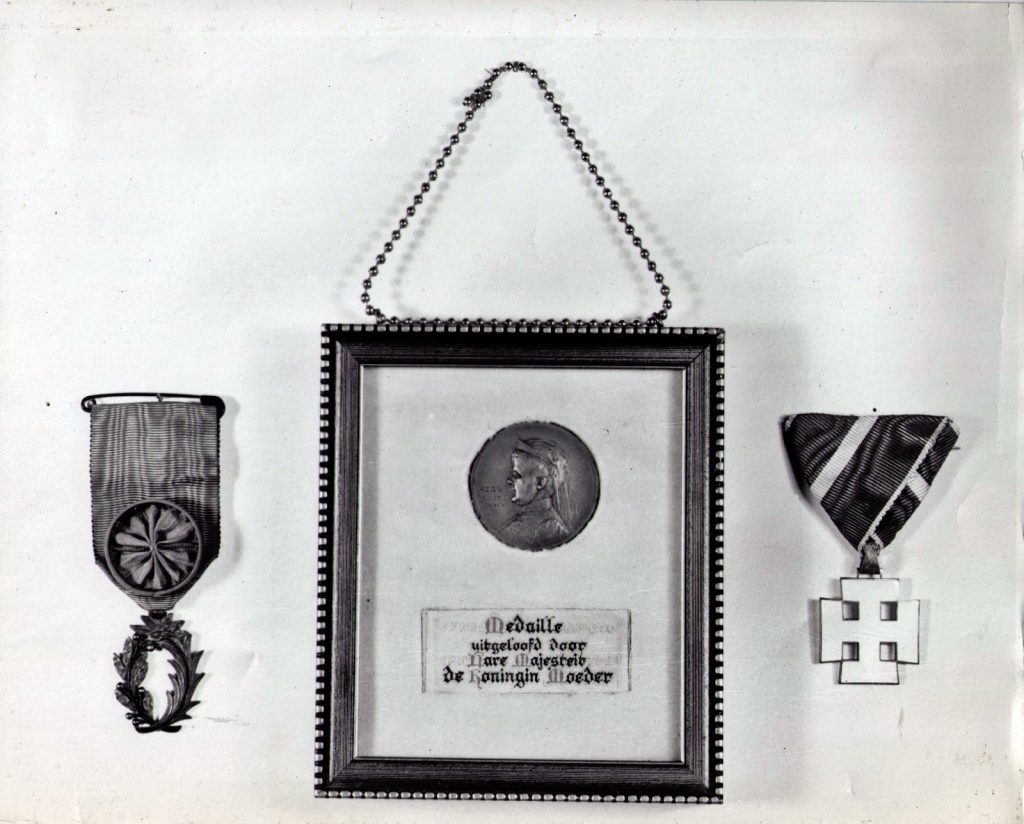

From 1918 to 1940, his exhibits made news of interest to collectors and the general public. They were on view in Amsterdam, The Hague, and Enschede (Holland); in Manchester, England, where the famous Sir Harry Lauder participated at a benefit for wounded soldiers and sailors; in Paris, where he received the Order of the “Officer de l’Instruction Publique de France,” at the hands of President Raymond Poincare; in Vienna, where the President of the Republic of Austria, Dr. Iquaz Seipel, awarded him the Order of the “Offizierkreuz des Ordens fuer Verdienste um die Republik Oesterreich.” In 1928, a silver medal was presented to him by the Queen Mother Emma of the Netherlands; in 1929 he was decorated by the Netherlands Institution for the Protection of Animals. All these honors were conferred in recognition of his exhibitions for the public interest. In 1933 at The Hague, he received special notice for his collection of photographs, prints, medals, coins, letters, manuscripts, etc. pertaining to the founder of the House of Orange, William the Silent, and his descendants who ruled the Netherlands, including Princess Juliana (later Queen Juliana), born April 30, 1909. Between 1929 and 1940 he served as correspondent-representative of the Oranje Nassau Museum at The Hague. He donated medals, prints, autographs, letters, manuscripts, etc., which are still housed at the Museum.

On May 10, 1940, the vicissitudes of history pulled down the curtain on Mr. Frankenhuis’s normal activities. From that black day until May 1945, he, like millions of other Europeans, was deprived of all civil and human rights by the Nazi invasion of his beloved homeland. Already in the 1920’s he was aware of the shadows that had begun to form, portending the monstrous events to come, although their full impact was beyond imagining. World security was crumbling, with the heads of governments and the League of Nations powerless or unwilling to stem the aggressive provocations of the nations that were later to become Hitler’s allies. Unemployment, depression, unrest, a groping for political change made large sections of the population, notably in Germany and Austria, vulnerable to the ravings of Hitler. Step by step, the Führer destroyed the opposition until every vestige of democracy, legality, and decency was removed. Ever tighter he turned the screws against his selected scapegoat, the Jews. As he stirred up new waves of anti-Semitism, he silenced whatever voices remained in Germany to cry out against the excesses of the Nazi cult. When he decided he had “solved the Jewish question” in the Third Reich, he turned his attention to the rest of Europe.

World War II began with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Next came the conquest of Norway and the occupation of Denmark. On May 10, 1940, the German armies invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg without warning or provocation. Having foreseen this dreaded possibility, Maurice Frankenhuis had frantically taken steps to safeguard his collection. His coins, gold, medals and memorabilia were packed in 23 huge crates and moved – under an assumed owner’s name – to a bonded warehouse in another city. These precautions were deemed wise to thwart discovery by the Germans. However, with fanatical thoroughness the invaders ferreted these collections out of their hiding place, identified and confiscated them as Jewish property, and shipped them to Germany.

Concern for one’s property was completely dissipated by the overwhelming fear for one’s life. There was no escape for mankind. The Germans ordered all Jewish males in Holland (as they did in other countries) to report for deportation to labor camps. Maurice Frankenhuis courageously defied the decree and found refuge for his family in a small room in the home of a trusted Dutch family in The Hague. Here he, his wife and two small daughters remained hidden for 21 months, until they were discovered by the German police assisted by a Dutch Quisling, who was collaborating with the Nazis. All were arrested and imprisoned, first at Scheveningen, then at Westerbork, and finally at Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, where they were liberated in May 1945 by the Russian army. When at last the Frankenhuis family returned to Holland, they were dismayed to learn that theirs was one of the very few Jewish family units to have survived. Nearly 100,000 Dutch-Jewish citizens were murdered in the German concentration camps.

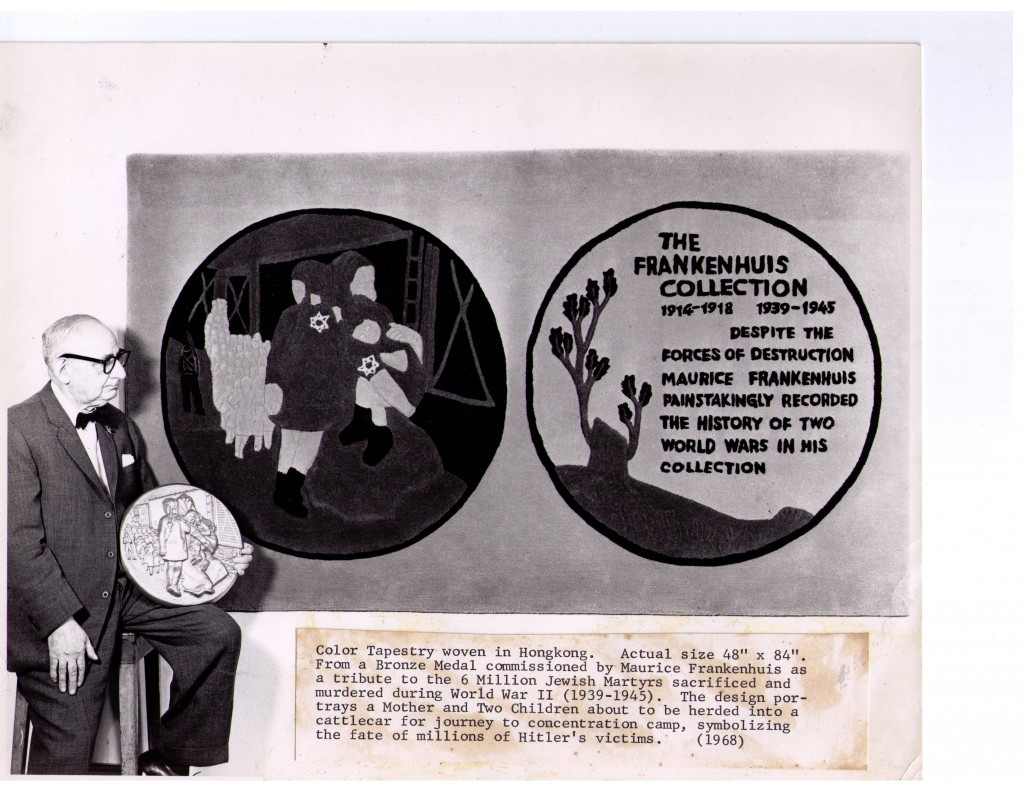

Maurice Frankenhuis, medalist, commissioned a medal as a tribute to his half-century of creative collecting (1914-1967).

Having gained the esteem of his counterparts throughout the world, he is recognized for his notable contributions to the archives of 20th century history. His entire life was spent close to the scenes of political upheaval: he saw kings dethroned, governments overthrown, the raging of two world wars, and the inferno of the Nazi holocaust. In this framework, he systematically built up his two major collections of medals and coins, symbols and insignia and other memorials to patriotism, nationalism, heroism, sacrifice, intrigue and betrayal, relating to Word War I (1914-1918) and World War II (1939-1945).

From over five decades of documenting his experiences, including a diary, reports and letters, Maurice Frankenhuis has made a dramatic contribution to the annals of history reflecting his enterprise and ingenuity. No journey was too tedious, no effort too great, that led to a coveted acquisition or to an audience with one or another of the political or military leaders whom he was vitally interested in meeting – often for a frank confrontation. Like a reporter on a news-scent, he followed a trail to abandoned army posts, war-torn villages, prisons, concentration camps, and war-crime trials. He traveled to Europe periodically not only to enrich his collections but his experience, as well, as an observer and commentator.

The Frankenhuis Collection is in itself a huge library containing large and comprehensive assortments of subjects such as war posters, emergency money (a feature of wartime), porcelains (curios used by the Germans for war propaganda), military decorations, manuscripts, stamps, autographs, gold, silver and bronze coins and complete files on aircraft, the royal houses of Orange Nassau, Hohenzollern, churches, synagogues, Judaica, townhalls and other institutions, besides letters from Lenin and Trotsky and a special collection pertaining to the Russian Revolution.

Maurice Frankenhuis donated material from his collection to various museums and institutions. The purpose, he reasoned, to serve as an educational resource and documentation of the most turbulent events of the 20th century, and particularly his firsthand account and personal experience of the Holocaust of Dutch Jewry.

The bulk of his World War II collection is yet to be made publicly available. The permanent repository of archives and artifacts will be available to visitors, historian – researchers, and those of the creative media community, and ultimately fulfill his desire to record this grim epoch, and keep alive the memory of the heroic men and women, martyred and murdered by the Nazis.