Medals handcrafted for Princess Beatrix whilst in hiding

From the Memoirs:

A MEDAL FOR PRINCESS BEATRIX

For 21 months, our family lived at 185, Galilaestraat, The Hague, all four of us cooped up in one room. We were hidden by trusted friends, whose vigilance postponed the day when we would be caught and sent off to concentration camps, and perhaps even to the gas chambers.

In a way, our plight was similar to that of the family of Anne Frank and thousands of others who had no alternative but to stay under cover during the German invasion of Holland which began, without any provocation, on May 10, 1940. All of Holland was stunned by the ruthless acts of brutality against the civilian population, and the Jews were singled out to receive the brunt of the blows. It was not war, it was murder. Our only course, at least temporarily, was to stay out of the way of these psychopaths against whom there was no defense: it was impossible either to reason with them or to subdue them by force.

And so we remained, completely cut off from the outside world. We were fugitives who could not flee. Our bare necessities were smuggled in to us. Any moment of the day or night we could expect to hear the sinister tramp of the Nazi boot on our stair, too, to pronounce our doom, as had already happened to thousands of our co-religionists.

In such an atmosphere, one would imagine that the human spirit would be stifled, the mind dulled, and all parts of the body paralyzed. Strangely enough that was not altogether the case with us. The will to live, if anything, sharpened our senses.

Despite the misery of our clandestine existence, we continued to talk, to love, to pray and to hope. Nor could the hideous shadow of lurking danger strangle the freedom of imaginative creativity which is the special gift of children and of which our two little daughters had their share.

One day, our 13-year old daughter Bertie announced that she wanted to make a special medal for another little Dutch girl – Princess Beatrix, the eldest of the three daughters of H.R.H. Princess Juliana, and granddaughter of our reigning Queen Wilhelmina. Bertie did not resent the fact that Beatrix, aged 5, was safe with her parents and sisters in Canada. They had all moved out of the Palace at The Hague shortly after the Germans had moved into Holland.

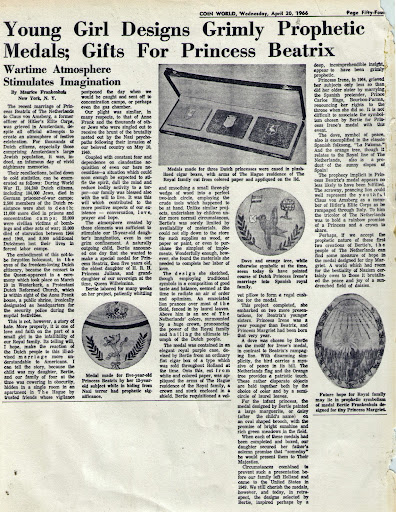

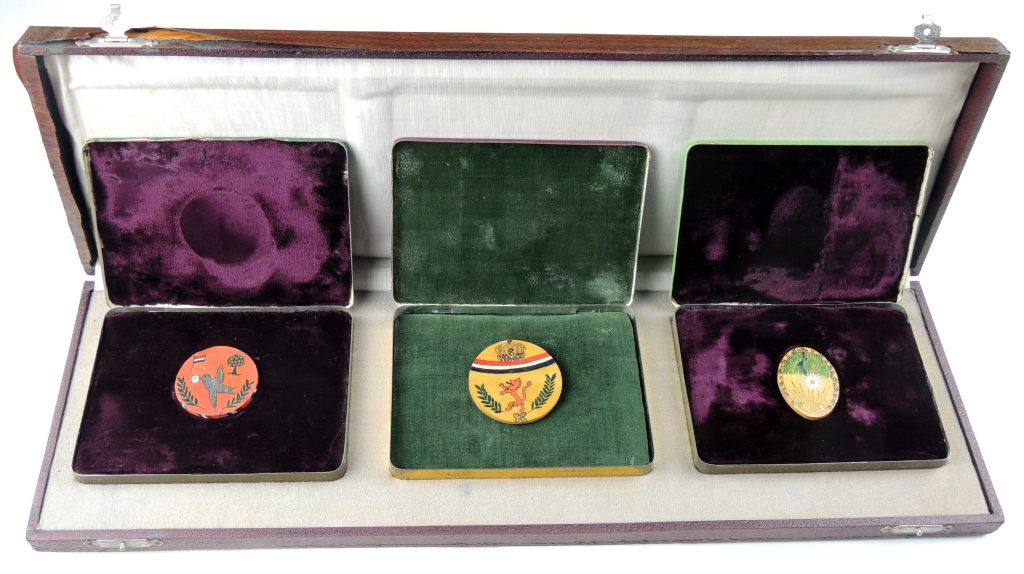

For weeks and weeks, Bertie labored over the little 3-ply wedge of wood, patiently whittling and smoothing it with crude tools into a perfect circle 2″ in diameter. She sketched her design, using familiar symbols, but perhaps in a new Gestalt expressive of a new world which was indeed chaotic. Nevertheless the child had arranged the elements into a composition of such good taste and balance that it seemed to radiate an air of order and optimism. While an emaciated lion is prancing over most of the field, and laurel leaves fence him in, a huge crown looms over an arc of the Netherlands colors, pronouncing the power of the royal family and hailing the ultimate triumph of the Dutch People.

This little wooden decoration was turned out under the most impossible conditions. You just couldn’t go to the store to buy the wood, the paper, the paint, or even the simplest of implements that were necessary. But somehow they “materialized” for Bertie, and in time she finished her labor of love. With the remaining scraps of materials, she went ahead and created special medals also for the two younger sisters of Beatrix: Princess Irene, then 4 years old; and Princess Margriet born that very year.

For Irene’s medal, a dove is chosen as the motif, in contrast to Beatrix’s rampaging lion: with disarming simplicity the bird carries a peace missive in its beak. The Netherlands flag and the Orange tree provide a patriotic touch. These rather disparate objects are held together both by the color and by a semi-circle of laurel branches.

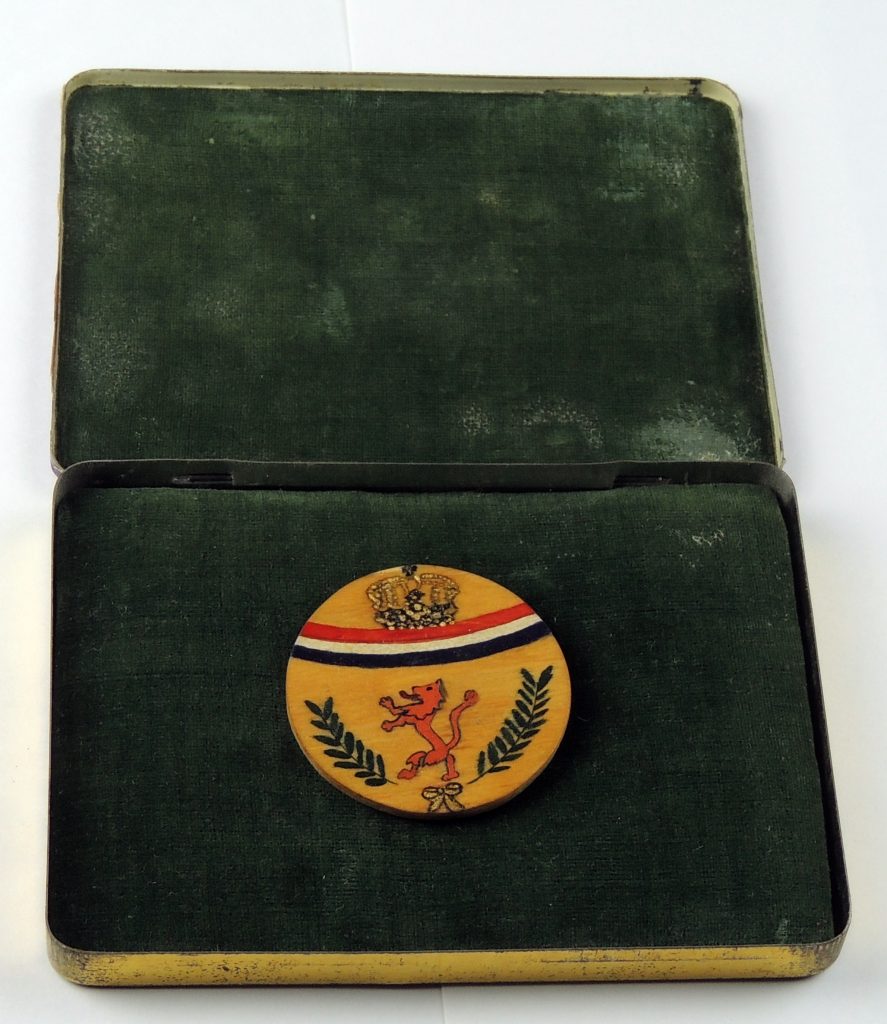

The medal which Bertie made for the baby Princess Margriet is delightful and gentle. A large marguerite (or daisy) is painted on an oval shaped brooch in natural colors. A bright day of gleaming sunbeams and verdant meadows heightens the bucolic effect. The border motif consists of a wreath of orange fruit and leaves.

To invest them with elegance, an appropriate case was required for each of the medals. Quite ingeniously, Bertie made use of some ordinary, flat cigar boxes, used for 10 thin cigars and sold throughout Holland. These she painted in solid rich colors: royal purple for Beatrix, blue-green for Irene, yellow-green for Margriet. And on the cover of each box, skillfully cut out of white and colored paper, she designed and appliquéd the coat-of-arms of the Hague-residence of the royal family, depicting the crown and the stork enclosed in a shield. The final regal note is the box linings. A layer of rich velvet was smoothly applied and glued for permanence, to cushion and frame each of the brooches and to line the inside of the box-cover. We had permitted Bertie to cut up a pillow or two to get her velvet.

And so, after months of industry, Bertie’s job was finished. All she had to do now was wait for the war to end, when she fervently hoped I would be able to help her present the medals in person to the Princesses.

The interval until the end of the war was indescribably harrowing. We heard about the freight cars that transported so many Dutch Jews to their destruction. We heard of the tragic separations of babes from their mothers, little children from their parents, and the continuous traffic to the camps. We could not continue to elude the Nazi police and the Quislings. We were discovered and arrested in 1944. It was September 4, when my wife and I and our two young daughters were also placed in cramped freight cars with 60 other Jews in each truck, in an insulting, degenerate and inhuman experience that defies description. The agony of this trip, of prison and two concentration camps has been portrayed by too many similar victims to require further elaboration here. In the end, we were the only Jewish family unit in the Netherlands to return home intact after the war. Our last stop had been Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, from which we were liberated by the Russians: we found ourselves back at home on June 27, 1945. Restored to our possessions, we were happy to find Bertie’s brooches for the Princesses.

Bertie lost no time to remind me of my promise to help her bring the medals to the Princesses. Protocol dictated that I apply to the Court in writing. My letter to Princess Juliana’s Secretary was written in pencil and on inferior paper due to the prevailing shortages. A few days later, on July 17, I received a reply: As the Princess was travelling abroad, wrote Secretary J. C. Baron Baud, he was unable to discuss with her my offer of the presents. He suggested that we wait for news of the royal family’s return and that he was hereby giving us permission to send the presents to the Palace by mail.

For over two years, Bertie had had her heart set on a personal meeting with Princess Juliana and the little Princesses. She was disappointed at the frustration of her hope and decided not to send the medals by mail, but to hold on to them. Perhaps there would be another chance. But there never was.

Bertie was busy at school and with the serious job of growing up. We left Holland in 1949 and, upon our arrival in New York, Bertie entered Barnard College. Instead of medals, she began to collect degrees and scholastic honors: B.S. cum laude at Barnard; M.S. at Brown University; Ph. D. at Syracuse University, and Phi Beta Kappa. Today she is a Professor at the University of Syracuse, a noted biologist and has published and conducted important works in cancer research. A brief account appears in “Who’s Who of American Women” (1966-1967 edition).

As to the medals, they have remained in the family, and I treasure them as part of my collection of memorabilia related to the Royal family of the Netherlands. Much of my zeal as a collector was directed to this interesting family with whom I was brought into close focus, before the outbreak of World War II, when I served as correspondent of the Oranje Nassau Museum in The Hague.

From Queen Mother Emma (grandmother of Queen Juliana) I received a special medal in recognition of my work in organizing a large trade exhibition. It is an attractive silver piece with the Queen Mother’s profile on one side and on the other side the inscription “Historical Association IBEX” and the date June 16-24, 1928.

Also I served on a Committee which arranged a special reception to Queen Wilhelmina (mother of today’s Queen Juliana) on the occasion of her official visit to the City of Enschede where I had lived for the greater part of my life. In the 1920’s it was an important industrial city, and many Dutch Jews were active and successful in its business and communal life. It was here that the first large-scale raid on Jews in the Netherlands occurred on September 15, 1941, when the Nazis arrested 108 Jewish men and boys. I knew them all personally: they were all shipped to Mauthausen, one of the most infamous of the German extermination camps. Not one of these 108 men survived.

Wilhelmina, who ascended the throne in 1890, ruled through two world wars (the Netherlands was not involved in World War I — the Germans permitted it to observe neutrality). But, as will be noted below, she did play a part in World War II when she headed the government-in-exile in London.

Wilhelmina abdicated the throne in 1948, in favor of her daughter Juliana, who had created a furor in 1937 when she married a German, Prince Bernhard zur Lippe-Biesterfeld. This was, of course, prior to the war but at the height of the Hitler period when there was hardly one upper-class German who did not have the taint of Nazism. There were demonstrations by the democratic and liberal elements throughout Holland.

Reporting a pre-nuptial celebration at the time, the press disclosed that the proceedings were far from harmonious. The orchestra leader, Dr. Van Anrooy, refused to conduct the program that, in deference to the bridegroom, included the Nazi “Horst Wessel” song and “Deutschland uber Alles.” A Captain Boer, conductor of the Royal Military Band, took over for these numbers, a gesture that certainly did not boost his rating with the public. There were 2,500 invited guests. They were spared the indignity of the display of the Nazi swastica in the hall of the Society of Arts and Sciences, but they were obliged to listen to the anti-Semitic Nazi music.

I would like to mention here my close friend, chief Rabbi I. Maarsen, of The Hague, who had been invited to the celebration. He declined: naturally he would find the “Horst Wessel” abhorrent. Instead of recognizing his deed as courageous, he was openly criticized in certain quarters for having slighted the royal family. This attitude hurt him deeply. It was his tragic fate, ultimately, to fall into the hands of the Germans. He, his wife and two daughters (who had been playmates of my children) were deported and killed. I shall never forget Rabbi Maarsen, his righteousness, kindness and wisdom.

Queen Wilhelmina, presiding over the ceremonies, greeted the “distinguished” foreign guests coldly. She sat in stony silence when the bridegroom’s uncle and the German Minister, as well as her own sister, Princess von Erbach-Schoenberg, gave the Nazi salute.

The war was over when Juliana was crowned Queen of the Netherlands upon the abdication of her mother in 1948. Bernhard, Prince Consort, had gained acceptance among the people. They had forgotten that he once worked as a salesman for I. G. Farben. They remembered that he had frequently condemned the pro-Hitler Germans; they knew he could not prevent their invasion of the Netherlands; and they realized that he had put up as much resistance as possible, prior to leaving for Canada to join his family, where, incidentally the princely family spent some of their happiest years. However, the Dutch people are satisfied with him: he has demonstrated again and again that he is loyal to his adopted country, rather than to his native land.

Since 1890 the royal succession has been on the distaff side. The House of Orange continued to bear daughters only, through the union of Juliana and Prince Bernhard. Therefore, there is now every likelihood that as the eldest, Princess Beatrix will succeed her mother to the throne. Her marital commitment is a matter of great concern to the state and the public. The announcement of her betrothal to the German diplomat, Claus von Amsberg, came as a great shock, incomparably greater than was caused by her mother Juliana’s alliance with the German Bernhard three decades earlier.

In a despatch from The Hague, printed in the World-Telegram (New York) on June 23, 1965, Inez Robb says:

“The Dutch have never forgotten or forgiven . . . this is a country in which the people have made a shrine of the Anne Frank house in Amsterdam; in which scarcely a community is without a monument to the resistance movement which fought the occupying forces.”

Further, the author reminds us of some shocking facts, as set forth in “Delta,” a quarterly review of arts, life and thought, published in the Netherlands:

“Died in German prisoner-of-war camps 104,240 including 104,000 Dutch Jews. Resistance members shot in the Netherlands 2,500. Died in prisons and concentration camps 11,000. Civilian victims of bombings and other acts of war 23,000. Victims of starvation 1944-56 15,000. Victims of forced labor 8,000.”

The Dutch cannot overlook the fact that Claus von Amsberg had been

(1) sent to Germany by his parents all the way from Tanganyika to receive a thorough Nazi education; (2) had joined the Nazi Youth movement; and (3) even though still a teenager, had served in the Hitler Elite Corps as an officer until he was captured by the Allies on the Italian front and imprisoned until the end of the war.

Public opinion, at first averse to the marriage, has slowly veered towards accepting it. However, opposition from many sensitive quarters refuses to give way. Instead of feeling honored, the citizens of Amsterdam were irked by the choice of their city as the scene of the wedding.

Edward Cowan in a special despatch to the New York Times from Amsterdam on November 14, 1965, writes:

“Amsterdam is the most left-wing of Holland’s cities. During the German occupation it, and above all its large Jewish population, suffered what is recalled as especially harsh treatment.”

“It is widely thought that the selection of Amsterdam for the marriage of the Crown Princess to a former member of the Hitler Youth and the German Army was a blunder . . . the national Government had committed its prestige, perhaps prematurely, to Amsterdam.”

The religious ceremony will take place in Westerkerk, a Protestant Dutch Reformed Church, which is within sight of the Anne Frank house: it is ironical that this public shrine has been designated as headquarters for the security police during the festivities.

Amsterdam has historically been the home of most of the Dutch Jews. Settling there in large groups during the Spanish Inquisition, the Jews had through the centuries become thoroughly integrated into the community, while remaining free to maintain their Jewish identity and traditions. They have contributed significantly to the economy and culture of their adopted home and were held in high regard. Rembrandt, for instance, had 300 years ago memorialized the Jewish patriarchal figures, whom he painted with veneration in his immortal masterpieces. Besides the Jews, the Puritans in the 17th century, escaping from persecution in England, found refuge in Holland while organizing their transportation to the New World. Centuries later, poor and downtrodden emigrants from Central Europe (mostly Jewish) found a haven in Holland, en route to the Land of Liberty, the United States, which they reached in steerage accommodations on the ocean-going liners. In the twentieth century, Amsterdam, an up-to-date, gay and cosmopolitan city, opened its doors to numerous wealthy German Jews, who thought they could sit out the Hitler menace away from home, prior to the outbreak of the war. Holland had earned its reputation as a liberal, peace-loving and friendly country.

Ever since the end of the war, the Dutch were struggling to restore the benign image of the past, and suddenly it was faced by two successive crises:

In 1964, Princess Irene became a Catholic and married the Spanish pretender, Prince Carlos Hugo, Bourbon-Parma. Wrote Harriet van Horne in the New York World-Telegram of February 21, 1966:

“Historically the Dutch dislike the Spaniards almost as intensely as they dislike the Germans. Spain was a cruel master in the years she held Holland in fief. And William the Silent fell to a Spanish assassin. Worse, Irene’s husband is part of the reactionary clique, that’s close to Gen. Franco.”

Irene, at least, had the forbearance to write herself out of any royal claims. She chose love and renounced her rights to the throne of Holland.

The second calamity was also Cupid’s doing. Beatrix, like her sister, chose love, but she strove to win Parliamentary approval, so that she would not have to sacrifice the crown. The government by a large majority, even though besieged by protests — 66,000 signed petitions – voted its approval of the marriage. This decision over-rode other strong protests, such as those of members of the former Resistance Movement who are regarded as anti-Fascists and war heroes by the Dutch people, and who addressed their appeal to Queen Juliana, Prince Bernhard, and the Council of State.

In an effort, perhaps to neutralize the vehemence of the opposition, Queen Juliana, a diplomat and also a lover of peace, invited the three leading Rabbis of Holland to attend the wedding. But they spurned her invitation, having among themselves agreed to stay away from the church. How could they sanction by their presence, they asked, the union of their future queen to a man who was (if not now) actively part of the criminal Nazi machine? The rabbis have been adamant in their refusal to take part in the wedding festivities. They are backed in their stand by the Jewish-Dutch community, the Union of Liberal Religious Jews in Holland, and the Jewish Portuguese Community. Sections of the non-Jewish population also applaud the action of these Jewish leaders. That the Rabbis survived the holocaust is a miracle. That they cannot forgive the unforgettable slaughter of their people is axiomatic. And they are safe from the kind of outside criticism that had been hurled upon the unfortunate Rabbi I. Maarssen when he took his stand against the “Horst Wessel” and what it stood for, during the nuptial ceremonies of Princess Juliana in 1937.

As to the Germans, they are most enthusiastic about the alliance. Naturally! They lost no time to commemorate the event with a medal in honor of Beatrix and Herr Claus.

A medal is a contemporary document. In a set of medals which are in my collection, as illustrated herein, one can trace the saga of the Dutch matriarchy. The medal of Queen Mother Emma was presented to me by her. Her likeness bears the stamp of Victorian primness: the crowned headgear with veil and the high neck blouse are reminiscent of the aristocratic dowager-style that prevailed in an earlier period but which disappeared in the 1920’s.

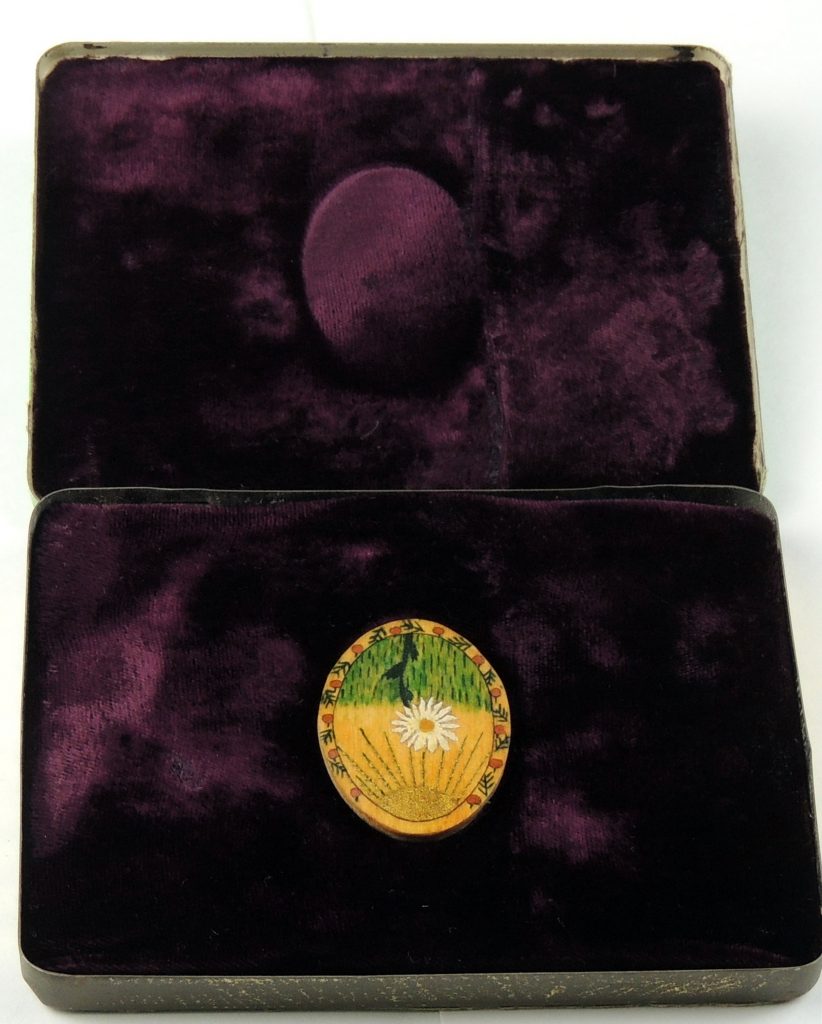

My second medal is of Queen Wilhelmina. Instead of a crown she wears a war helmet, like the Greek goddess Athena. Actually this consists of a Dutch silver guilder coin, with part of the obverse legend obliterated, leaving the message ‘”Wilhelmina in London.” The Dutch queen, like the rest of the royal household, had vacated the Palace when the German army moved into Holland. Immediately she set up a government-in-exile in London and headed the Dutch resistance movement in their operations against the Nazis.

In 1959, a beautiful coin was minted (in gold) which bears the profile of Queen Juliana, in a classic design that harmonizes with the legend encircling it — reading: JULIANA, QUEEN OF THE NETHERLANDS. The other side of the coin shows that ever-present king of the Beasts. This time he is a fighting lion, wearing a crown and armed with a club against a menacing serpent. A caption designates the Queen as the BULWARK OF DEMOCRACY (translated from Dutch).

The medal for Beatrix and Heer von Amsberg, struck off by the Germans, completes the gallery of the “Daughters of Orange.” one thousand copies of this medal were issued as soon as the betrothal was officially announced in June, 1965. Inscribed in Dutch, the bridegroom is referred to Heer Claus von Amsberg, giving him the flavor of already being Dutch and recognizing him as a commoner. It is a bulky piece of silver, on the front of which we see an over-realistic, glowing likeness of Beatrix, which stresses with accuracy the double strand of pearls at her throat, an earring dangling from her right ear-lobe, a low-cut dress, a stylish hairdo, and an overall effect of an attractive buxom bourgeois — hardly a Princess. On the reverse side: the royal emblem of two lions poised before the throne, surmounted by a crown.

Perhaps this piece will be of interest to collectors and its material value may even be increased with profit to its owners. But the first crude medal, which one little girl, hidden from the Nazis, formed with her heart and hands, as a gift to her Princess, unfolds a more poignant and epic story — of the suffering and heroism of a people.

Strangely enough, the prophecy implicit in the design is indeed being fulfilled. The emaciated, prancing lion could well be the youthful Claus von Amsberg, in Hitler’s Elite Corps, rampaging through Italy, for whom eventually the tri-color of the Netherlands would hold out a rainbow promise of a princess and a crown to share. Does he merit this reward?

Note: The medal made by Bertie for Princess Irene seems equally prophetic. The dove, while a symbol of peace, is also a popular Spanish folk-music theme, as exemplified by the classic “La Paloma.” And the Oranges, while relating to the royal line of the Netherlands, are at the same time one of the important products of Spain. It all ties in very neatly!

Letter requesting visit to present 3 medals to Princess Juliana

TRANSLATION FROM DUTCH INTO ENGLISH

M. Frankenhuis

The Hague

24, van der Wyckstr

July 12, 1945

To the Honorable

Mr. J. C. Baron Baud

Private Secretary to H.R.H. Princess Juliana

Palace The Loo

Apeldoorn

Honorable Sir:

I wish to bring the following to your attention. The undersigned has just returned to the Netherlands, with his wife and two daughters, from the concentration camp Theresienstadt (Czechoslovakia), after having been confined in prison, punishment prison, labor camp and finally in the said concentration camp as political prisoners of Jewish-Netherlands descent.

Prior to our arrest we were in hiding in the Hague for about one year and nine months. During this period my youngest daughter, Bertie Frankenhuis, made three brooches intended for each of the three Princesses, i.e., H.R.H. Princess Beatrix, H.R.H. Irene and H.R.H. Margriet.

They are made from the simplest materials, decorated with emblems and symbolic designs; the boxes too were especially designed, each brooch housed in its box. They are fabricated entirely by my 14 year old daughter, who had spent months on this project. I promised her at the time that if we should have the good fortune to be freed from the German yoke, I would make every effort to enable her to present her brooches to H.R.H. Princess Juliana, as well as the Princesses Beatrix, Irene and Margriet, personally after the termination of the war.

In 1944 we were arrested and imprisoned in Scheveningen and various camps. Upon our return home this week, she inquired about these medals and we were most fortunate to find them unimpaired and undamaged.

During the long period of horror and persecution, she nursed the hope the day would dawn when she would present them to the Royal Family.

If you will allow me an interview, I will be glad to give you full information concerning this request.

For your information, permit me to add that I have an extensive collection of the Orange House and have been correspondent of the Oranje Nassau Museum in the Hague. I have organized many exhibitions for charitable purposes, for instance, the Netherlands Relief Fund. I was a board member of the committee arranging the reception of Queen Wilhelmina in Enschede at the time of her visit there, and am the recipient of a silver medal awarded by Her Majesty, Queen Emma, in connection with an exhibition organized by me.

I would very much appreciate your kind consideration as to the possibility of the proposed presentation by my daughter, at any time you may state, and am willing to provide, with pleasure, all further information.

In the meantime, I remain, gratefully,

Yours sincerely,

(signed) M. Frankenhuis

Reply from Secretary to Princess Juliana

TRANSLATION FROM DUTCH INTO ENGLISH

Secretariat

of

H.R.H. Princess Juliana

Apeldoorn, July 17, 1945

THE LOO

To Mr. M. Frankenhuis

van der Mijckstraat 24

The Hague

Referring to your letter of July 12, in connection with your offer of gifts for Her Royal Highness Princess Juliana and the little Princesses, I have the honor to inform you that Her Royal Highness is at present on a trip abroad, and we are therefore unable to discuss the matter of this presentation with Her Royal Highness. In the meantime, may I inform you that personal

presentation of gifts is not permitted as a rule and can be allowed only in exceptional cases. Therefore, in consideration of the gifts mentioned, I will give you permission to forward them to Her Royal Highness and the little Princesses, as soon as you will be informed through the newspapers that Her Royal Highness and the little Princesses have returned to the Fatherland.

The Private Secretary of

H.R.H. Princess Juliana

(signed)

(Col. Mr. J. C. Baron Baud)

Excerpt from the Frankenhuis Collection Memoirs, Volume 21